As the rhythmic beats of talking drums echo across Epe’s ancient cobblestone, now tarred streets, and the aroma of celebratory feasts lingers in the air, it’s not just another festival. It’s Kayokayo, a jubilant, deeply symbolic event that pulses with the heartbeat of a history forged in fire, voyage, and cultural renaissance.

At first glance, Kayokayo might seem like a colorful street party. But scratch the surface and you’ll uncover a powerful narrative that continues to shape the spiritual, traditional, and social fabric of this ancient coastal town.

To understand Kayokayo, one must travel back to 1851, when Oba Kosoko, then king of Lagos, was dethroned after a bloody British bombardment of the city. With thousands of followers, he fled the island after a formidable but waning resistance and sought refuge in Epe. What followed wasn’t a retreat, but a rebirth.

“Kosoko didn’t just hide in Epe,” says Prof. M.O. Jimoh, a historian of Yoruba Islam. “He reestablished a functioning royal system, brought Islamic scholarship, and turned Epe into a cultural capital.” (Jimoh, 2016). His arrival, marked by traditional fanfare and spiritual rituals, is the inspiration behind Kayokayo, meaning “to eat in honor” or “to feast splendidly.”

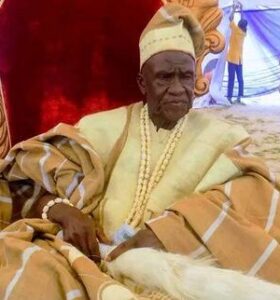

At the heart of the celebration are sacred rites that echo Kosoko’s regal roots. From the lighting of the “Etufu” lamp to majestic processions led by the Olu-Epe and Epe’s royal council, the festival revives centuries-old Yoruba customs. Masquerades such as “eyo” and “epo” parade the streets, connecting the living to their ancestors.

According to Dr. B.O. Adebua of the Yoruba Studies Review, “Kayokayo is a live museum of royal Lagosian culture transplanted into Epe.” (Adebua, 2017)

Interestingly, Kayokayo is not just a cultural display; it’s also a religious observance. Kosoko was a devout Muslim, and so were many of his followers. Over the decades, Islam embedded itself in the DNA of Epe. Today, Kayokayo, often celebrated during the month of Muharram and Ashura day, opens with Qur’anic recitations and Friday sermons at the prestigious First Epe central mosque, Oke-Balogun, reflecting the town’s spiritual evolution.

The Kayokayo Festival doesn’t just look inward; it reaches outward. Each year, Epe witnesses a mass return of its diaspora Eko-Epe descendants of Kosoko’s loyalists, alongside other esteemed followers who now live in Lagos and abroad. The town swells with visitors, family reunions, and homecomings.

It also boosts the local economy. Markets thrive. Hotels fill. Artisans and food vendors seize the moment. “Festivals like Kayokayo are cultural engines,” says Prof. Adeyeri, who studies cultural tourism in Lagos (Adeyeri, 2012). For many, it’s a time to reflect not just on ancestry, but on identity. As OO Metilelu noted in a recent ecotourism study, the festival has become “a binding thread for Epe’s cultural tourism and heritage branding.” (Metilelu, 2021).

Today, Kayokayo stands tall not just as a spectacle of culture but as a quiet form of resistance against erasure, against colonial forgetfulness, and against cultural amnesia.

It is Lagosian history told from the shoreline, not the throne. It is Yoruba tradition layered with Islamic devotion. It is a community rising from a resilient voyage in exile. And above all, it is a festival that reminds Nigeria, and the world, that history lives not just in textbooks, but in music, culture, and memory. Another glorious edition beckons in 2025, brace up!